The first conceptual theme that I began to research while processing my experience as a sex laborer is what I have come to call “the fetishization of safety.” This was born as the juxtaposition of two ideas. The first is in a literal sense: I worked as a laborer whose job it was to fabricate “safety” during the production of “fetish” movies. As I outlined in the previous chapter, I had a lot of different responsibilities; however, my primary responsibility above all else was to ensure the safety and well-being of everyone on set, most importantly the safety of the model. This process of creating safety could be as noticeable and straightforward as making bondage that was appropriate and well designed to fit the specific nuances of a model’s body. Or the process could be more behind-the-scenes, such as making sure everyone wore gloves when touching a model if the director or model requested that safety protocol on any given day. Regardless of how it manifested, the construction of safety was always on the mind of myself, my boss, and my coworkers.

The second source that inspired my thinking regarding the fetishization of safety came from a documentary film made by BBC director Adam Curtis called, The Power of Nightmares (2004). The documentary attempts to examine the world in the aftermath of the 2001 destruction of the World Trade Center in New York City. Curtis’ main thesis dissects the conceptual outcome that permeated from the United State’s subsequent “war on terror,” and how now, “Instead of delivering dreams, politicians now promise to protect us from nightmares.” The documentary goes on to show how both neo-conservatives in the Untited States and radical Islamists in the Middle East have weaponized the “fear of what might happen,” as opposed to what “is happening,” as a way to consolidate power and garner public support. In another era, former President Richard Nixon spoke of the necessity to, “Reduce the level of fear by reducing the causes of fear.” The idea utilizes a type of proactive thinking that is sometimes referred to as a “paradigm of prevention.” This sort of rationale requires leaders to “Look into the future and imagine the worst that might happen and act ahead of time to prevent it.” Since 2001, Curtis asserts that this has rapidly snowballed into policy decisions and incarcerations that are not based on what “is” and are instead based on what “if.” He asserts that we have come to fear the worst about things that may never exist and the leaders with the most polarizing and terrorizing visions of the future–however implausible and unsupported by data they might be–have become the most powerful.

Curtis’ documentaries are powerful and very persuasive. As I am not a historian nor an expert in political science, I cannot speak to the absolute validity of his claims. However, as an artist, I can observe the nuanced aspects of my life and see shadows of his observations reflected all around me. On a personal level, I have a desire to make safe decisions, keep the people who participate in my art projects safe, cause as little harm as possible, and keep marching towards the as yet unrealized egalitarian society that we have been promised for the past 245 years. I find that there is a question embedded within Curtis’ documentary that I cannot find an easy answer for: is safety a permanent, temporary, or non-existent condition manifested by the universe? Is there anything intrinsically “safe” about a piece of matter existing in the universe or is safety a social contract similar to the previously discussed idea of “power” that is not actually “real?”

Within the course of Western History, it seems apparent that certain groups of people were often only able to create a certain measure of safety and stability on their own terms, by appropriating it from other groups of people or ecosystems through theft, destruction, genocide, repression, extinction, or enslavement. It would seem that things are “safe” only relative to the person or people defining what that means. If there was ever a term that was more contextually defined as “safety”, I do not know what it would be. This begs the question: what is the definition of “safety?” Is it freedom from physical harm? That I will not be beaten by the police while walking to the store? Or when I plug my desk lamp into the wall socket that I will not be killed by an electric shock? Or perhaps that I can breathe easy knowing that an apex predator like a lion is not going to eat me for dinner? Or knowing that next month I can pay for my car insurance? Or that I can put my key in the front door of my apartment and that the lock will turn? Or maybe when I go to the supermarket my preferred brand of toothpaste is on the shelf waiting for me, etc.? The point is that what I experience as “safe” always seems to be circumstantial and dependent on ideas, institutions, entities, or people external to me to escort me to that feeling of “safety.” I asked myself, what happened to the mental fortitude that I attempted to foster while working as a locksmith for nine years? How had I missed the mark so completely?

As I began to digest the idea of “fabricating safety” as my primary job responsibility while working in adult fetish movies, I saw a convergence and a conflict of ideas. On the one hand, safety does not exist. There seems to be nothing intrinsically safe about being alive. At the same time, much of the effort that I have expended in my life and art practice has been devoted to helping myself or others to be safe, stay safe, or creating safety as a commodity while working as a locksmith, a yoga teacher, an artist, a sex laborer, or otherwise. For instance, I think the aspect of locksmithing that frustrated customers the most was not that I was capable of quantifying exactly how much their security was worth when I quoted them a price to do a job. I do not even think they were taken aback by high prices when the job demanded it. On the contrary, what I believe people found the most unnerving was that I could quantify their safety, and it turns out–in a relative sense–their safety was worth very little. A couple hundred dollars to change all the locks on a person’s house is a far cry away from the “priceless” value that we often associate with the worth of a single human’s life.

With all these issues in mind in February of 2020–right before the COVID 19 Pandemic began–I created an installation called Safe: 1, which consisted of three sculptures, two photographs, and a three-channel video installation. I decided to deconstruct the uniform that I used to wear on set while working as a sex laborer and constructed three different actions that I performed by myself and recorded with a video camera in what appears to be a controlled studio setting. The videos document the transformation of the three articles of clothing that comprised my uniform and the subsequent effect the transformation had upon my body.

The first video is about the black nitrile gloves that I would wear to keep my hands sanitary while I was making these movies. For this video, I layered approximately 30 pairs of gloves one over the other on my hands until they were swollen and incapable of dexterity. After sitting with the final layer on for several minutes, I slowly peeled each one off one-by-one and placed them on a table in neat piles. This process took about 25 minutes to execute from start to finish and featured only myself dressed in a black jumpsuit sitting at a white table in front of a white background. For me, no amount of gloves were ever going to create the impermeable safe barrier that I fetishized, and the “safer” I made myself, the more incapable, impotent, and at-risk I became.

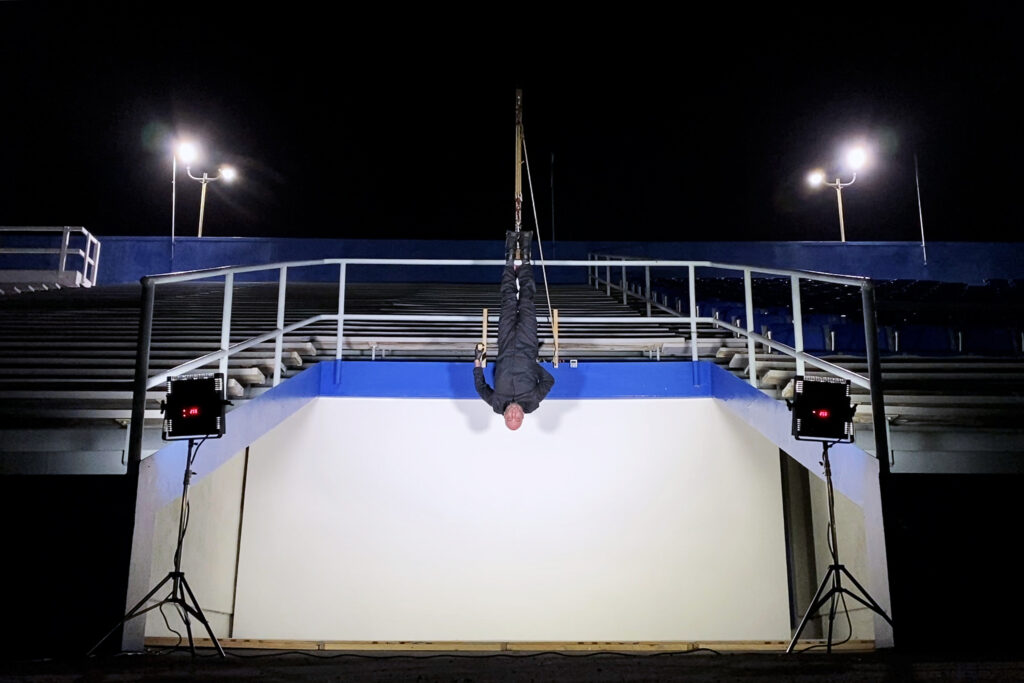

In the second video, I attached shackles to the bottoms of my orthopedic shoes, connected them to a block-and-tackle, and hoisted myself into a full-body suspension. I elevated myself about 16 feet off the ground so only my head was still captured in the frame of the camera. I stayed upside down for about 20 minutes and then lowered myself back down to the floor. This again was a simple composition of myself in the jumpsuit, set against a white backdrop, and a standard gray-colored floor. For this piece, I wanted the shoes that keep my feet safe to become fused with the bondage that I used to produce. I became both my own captor and subsequent liberator. Subject and object. A detention and suspension on my own terms, as opposed to a negotiated experience on someone else’s. As I had made my own bondage, I also fabricated my own safety.

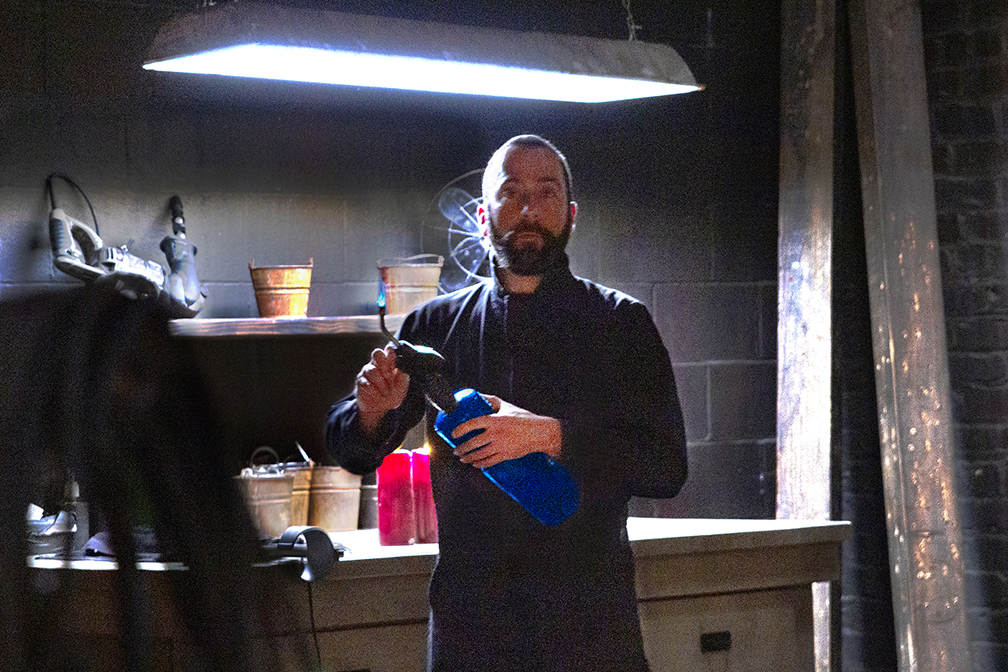

For the third video, I used a hand-held blow torch to slowly and methodically burn the jumpsuit off of my body by using the fire to cut a long seam from its bottom to top. I then removed the half-burned jumpsuit, piled it on the floor, and set it on fire. Most of the video is simply me sitting naked on the floor wearing only black shoes and gloves, watching as the jumpsuit burns like a campfire. By using the wrong tool in the wrong way, I was able to remove the symbolic remnants of my labor within adult films and allow it to pass peacefully into a quiet night while no one was watching but the camera.

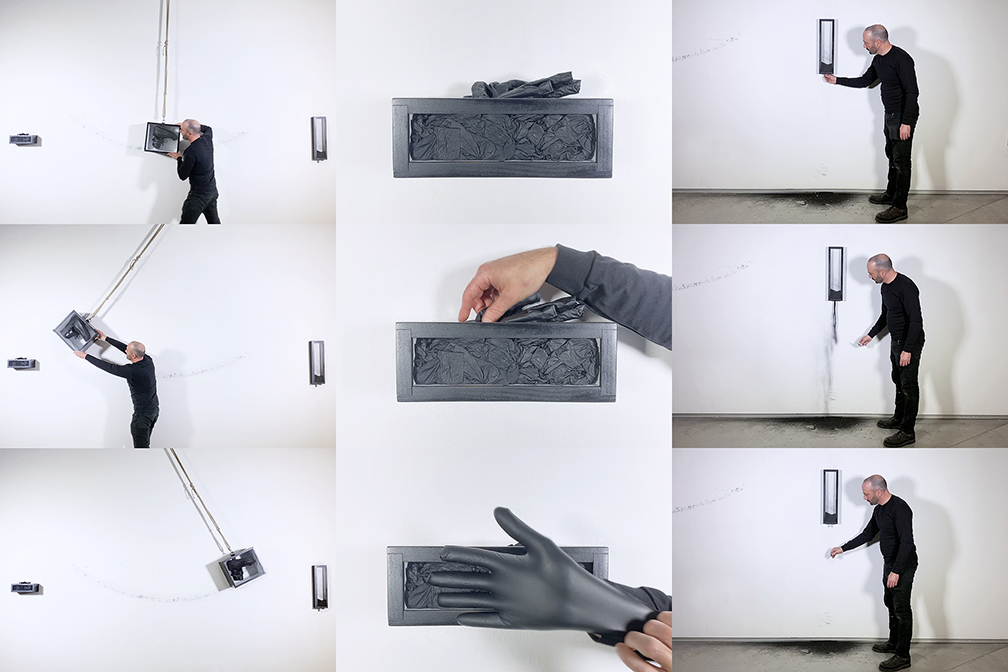

All of the videos were executed as simple, classically styled, single point, studio performance pieces, executed for the camera, and shot within the specific and deliberate setting of what appears to be an art studio, institution, or gallery. However this was an illusion. If a viewer spent time with the piece, they would begin to notice ambient sounds in videos–such as birds, planes, and cars–that expose the “studio” setting to be nothing more than a movie set. The pieces were actually recorded outside. I wanted to subtly show that the prestige and importance that is often permitted to galleries and artists studios is little more than an illusion constructed out of gray floors and white walls. The lighting that I mobilized in the videos draws direct inspiration from how I would often light a porn movie. Everything is illuminated in totality. I make no attempt to shape the subject in video with shadows, highlights, or contrast. Details are exposed and nothing is hidden or insinuated. These videos draw heavy inspiration from work such as I Am Making Art (1971) by John Baldessari, Bob Flanagan and Sheree Rose’s Visiting Hours (1994), Stelarc’s Suspension Performances (1980-Present), Bruce Nauman’s early video work, and Ana Mendieta’s pieces done for the camera. Each of the actions was edited into approximately 30-minute videos, projected onto three different gallery walls, and looped continuously over the duration of the exhibition.

In another room, there were three wall-mounted sculptures on display that housed the remnants of the uniform that remained after I filmed the videos. The sculptures were housed in formal, black, gallery shadow boxes with glass fronts. One was approximately the size and shape of a rectangular box that the nitrile gloves would come in when purchased from a store and had a hole cut out of the top so if viewers wanted to, they could take some gloves. The second box contained the shoes suspended upside down via a rope that extended through holes that I had cut in the top of the box. The rope extended all the way to the top of the wall where I had rigged a bracket. The entire shadow box could swing like a pendulum if a viewer chose to push it. As it swung against the wall, it left a black mark along the arc of its travel. The third shadow box was long and narrow and was full of the ashes that remained after the jumpsuit was completely burned. At the bottom of the box, there was a hole that had been stopped with a large white plug. If a viewer removed the plug, ash would spill out the bottom until they put the plug back in. All three of the sculptures appeared as if they were escaping from the sterile and contained structure of the formal shadow box. And, as the inside of the boxes escaped to the outside, their contents then had an effect on walls and floor, thus tainting a gallery’s often misplaced perception of neutrality. This process brought a viewer into direct contact with tactile objects that they at first were only able to indirectly experience while watching the videos.

Lastly, there was one photograph displayed in the room with the shadow-boxes capturing the pile of ash that remained after the suit completely burned and one behind-the-scenes photograph in the video room of myself working on a porn set, holding a lit blowtorch while wearing the black uniform.

More info about this series:

Since 1999, I have been using my jobs as research to inform my art practice. Having completed bodies of work regarding my professional careers as a cabinet maker, fine-dining busboy, locksmith, and yoga instructor, I most recently –from 2010-2018– worked behind the scenes helping to produce adult bondage and fetish movies as a full-time hourly employee. As a worker in this industry, my job title is often referred to as an “engineer” or a “rigger.” This entailed constructing or assembling the bondage in which models would be restrained during the filming of the movies. This role encompassed many different tasks; however, my most important responsibility was to create and fabricate safety for everyone on set, with the primary emphasis being placed on the safety of the model who would be in bondage. More information about this series can be found below:

When I began to moblize my employment in pornography as part of an art making process, I first had to determine if and how I might be able to ethically make art inspired by this research –as I have done in my other employment experiences– in ways that didn’t objectify anyone. At the outset, I spent a lot of time reflecting, researching, and defining how to situate my role as a worker in this very complicated context. To do this, I created the term “sex laborer.” By authoring this term, I was able to make a distinction between my job responsibilities and that of “sex workers.” Sex work is an identity and a form of employment for which I have tremendous respect, and I make this important distinction between my labor and that of sex workers because although some people in the world view my role in the production of fetish movies as sex work, others in the sex-industry disagree with that notion as I kept my clothes on and rarely appeared on camera. However, there have been other times in my life that my work in pornography has been treated with judgment by people outside of the industry in similar ways to the judgment that is sometimes placed upon sex workers. This left me in a complicated situation that I needed to come to terms with and to find a safe place from which to situate and contextualize my experiences. Complicating this matter further, I –unlike almost all of my co-workers– never assumed a stage-name or “porn-name” in an attempt to shelter my identity. I did this because it felt disingenuous to participate and examine adult films as “research” and then try to hide the fact that I was doing it. Although I stand by the ethics of this decision, this transparency places me in a precarious social position that required me to define an identity as a worker that seemed honest, while also firmly situating myself in solidarity with sex workers all over the world.

In February of 2020 –right before the COVID 19 Pandemic began– I created an installation called Safe: 1, which consisted of three sculptures, two photographs, and a three-channel video installation. I decided to deconstruct the uniform that I used to wear on set while working as a sex laborer and constructed three different actions that I performed by myself and recorded with a video camera in what appears to be a controlled studio setting. The videos document the transformation of the three articles of clothing that comprised my uniform and the subsequent effect the transformation had upon my body. Conceptually this project revolved around the theme that I have come to call “the fetishization of safety.” This was born as the juxtaposition of two ideas. The first is in a literal sense: I worked as a laborer whose job it was to fabricate “safety” during the production of “fetish” movies. Although I had a lot of different responsibilities, my primary responsibility above all else was to ensure the safety and well-being of everyone on set, most importantly the safety of the model. This process of creating safety could be as noticeable and straightforward as making bondage that was appropriate and well designed to fit the specific nuances of a model’s body. Or the process could be more behind-the-scenes, such as making sure everyone wore gloves when touching a model if the director or model requested that safety protocol on any given day. Regardless of how it manifested, the construction of safety was always on the mind of myself, my boss, and my coworkers.