The Yoga Teacher Series, 2007-2010

The projects in this series were inspired by experiences as a yoga instructor. There are five primary projects in this series that deconstruct each of the five senses: Smell, Sound, Vision, Touch, and Taste. There is also a sixth project that brought the series to fruition. More information about the origin of this employment and research can be found below:

In 2002, I decided to become a Locksmith as research to inform my art practice. At the same time, I also started to practice yoga. I did this to compare how we lock and guard our spaces, compared to how we lock and guard our bodies. As my time working as a locksmith drew to a close, I transitioned into working as a yoga teacher. When many of my friends and colleagues found out that I had begun to work and research as a locksmith, they encouraged me to do diabolical actions such as, stealing things or breaking into places, and then frame the action as “art”. Instead, the body of artwork that came out of this research yielded pieces that were by and large about liberation and breaking free of keys. This exploration of access, agency, freedom, and mobility was informed heavily by yogic philosophy to explicate the “attachment” that many people experience regarding keys and the relationships, places, and things that their keys allow them to access. Eventually I decided that my next career/research-project was going to be as a yoga instructor. After 4 years of schooling and apprenticing I started teaching yoga. I taught for almost 3 years and then stopped. When asked why I usually I site various reasons ranging from “I wasn’t good at it” to “it was ruining my personal yoga practice.” During this time I was also making artwork about being a yoga teacher. Again, many people had suggestions and desires about the kind of art pieces that could come out of this research. Many thought that I would make pieces about liberation and helping people, similar to the Locksmithing projects. Instead my research as a yoga instructor yielded works or art that were thematically similar to the Locksmithing pieces but used subtle (and not-so-subtle), passive-aggressive, forced-coercion tactics to herd or manipulate the viewer into doing things they would not normally do in public. Though in each of the Locksmithing pieces I was increasingly aware that I was deliberately posturing students into awkward and vulnerable positions in public, the yoga-teaching pieces were much less subtle and were often directly confrontational. This is what drove me away from yoga teaching. The power dynamic that exists in the yoga studio was too intense and seemed far too easy for me to manipulate (though I never did). I realized that what interested me most about my locksmithing research and yoga teaching was that both examinations explicated the ways that each of us create (or are forced to create) very private moments in very public ways. So, I began an investigation into how we share public space and maintain our privacy outside the confines of our own homes. The pieces in this section were directly born from my research as a yoga instructor. Most physically taxed my body in ways facilitated by yoga my practice and pushed the boundaries of audience members personal space. There are five projects in the series and they center around an examination of each of the five senses: smelling, hearing, seeing, touching, and tasting.

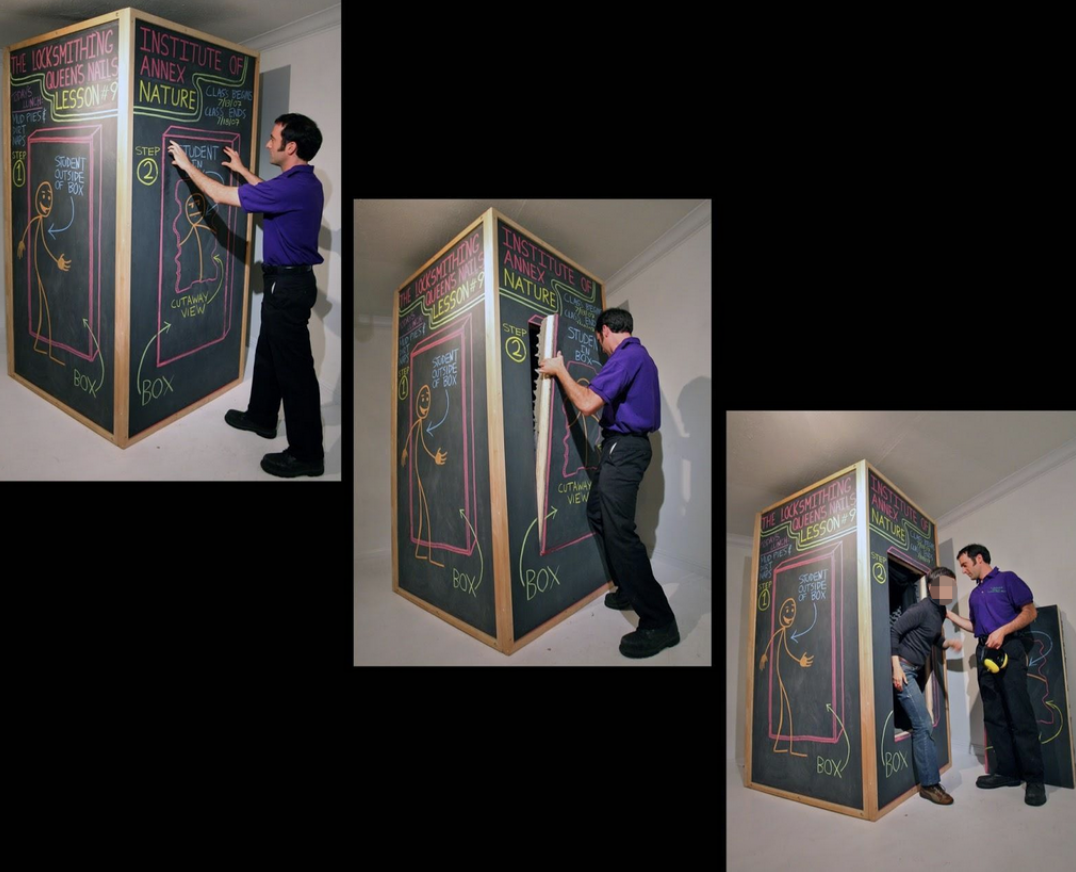

This new direction of my art research began in earnest In 2007. I had just completed the ninth lesson of The Locksmithing Institute in which I constructed a class and invited individual participants to take turns sitting for five minutes inside of a noise-canceling isolation chamber made from chalkboards. While one person was inside, other participants waited outside for their own turn in the chamber and joined me in a discussion about how we each construct our personal sense of security and mental fortitude.

After seeing this exhibition, artist and educator Jennifer Locke initiated a conversation with me regarding the embedded power dynamics that I was mobilizing in my lessons. It was from this conversation that I really began to make the connection between what I was studying as a locksmith and the relationships that are constructed and implemented between dominants and submissives in BDSM relationships. Much of my initial thinking regarding locksmithing had been inspired by Michel Foucault’s seminal work, Discipline and Punish (1975). Like many young thinkers, when I first read the book as an undergraduate, I was most inspired by his analysis of the systematic observational models that have been implemented within all of our institutions –schools, hospitals, prisons– to fluidly maintain power. Years later, after my conversation with Locke, I realized that although those initial ideas were powerful eye-openers for me, what I was actually most drawn to was how these institutions conceal power. In Foucault’s own words, “The punishment must proceed from the crime; the law must appear to be a necessity of things, and power must act while concealing itself beneath the gentle force of nature.” It occurred to me that the ability to make a power structure –which in my opinion is a temporary condition of our shared social structure– appear as if it was a permanent condition that has always always existed in the natural world, could be an incredibly powerful tool if wrenched from the hands of the dominant discourse.

As my time working as a locksmith drew to a close, I transitioned into working as a yoga teacher. The politics of BDSM only became increasingly apparent while I was teaching yoga and were reflected in the art projects that I made about this employment/research. I found the intense power dynamic in a yoga classroom to be very unnerving. Helping people into and out of painful and challenging situations created a power vacuum, which while acting as “the authority” struck me as problematic. This is ironic because I have no problem going to a class as a student and working with a teacher I really trust. In the end, I do not think I was ready for the responsibility and only worked as an instructor for a couple of years. The artwork that came out of this experience focused on intense power exchanges between myself and –mostly– unaware participants. An example of this is a project entitled 9/10 (2009), in which I locked myself inside a rolling cabinet’s hidden compartment as an examination of sense of “seeing.” The cabinet –and myself– were then left on a sidewalk in New York City. I didn’t exit the cabinet until someone unknowingly brought me from a public space into a private space.

When I started to recognize the patterns of dominant/submissive relationships which I was exploring within locks/keys and student/teacher dynamics, I began to reflect on the research and my personal history that had informed my decisions about this topic. It started long before I became a locksmith or learned about yoga while I was still working on my undergraduate degree at the San Francisco Art Institute. At the time, I was deeply invested in the first body of work that centered around my previous career as a woodworker in small furniture factories. Around this time artist and educator Pam Martin introduced me to a book called The Poetics of Space (1958) by Gaston Bachelard. In its pages, I dove deep into all the things I found magical about furniture, cabinets, corners, and cellars. As Bachelard asserts in the book, these are the spaces in which a child first learns to dream. The book was very inspiring and it is still something I skim through every so often when I want to dream. In the book’s introduction, Bachelard talks about a type of psychoanalytical investigation in which, “…we are able to isolate a sphere of pure sublimation; of a sublimation which sublimates nothing, which is relieved of the burden of passion, and freed from the pressure of desire.” I didn’t understand the quote at the time, but I kept thinking about it. Years later, while I was trying to help people during locksmithing jobs, it kept popping into my head as I’d be physically kneeling on the ground trying to open locks for customers who–while standing above me–were mentally incapable of creating a sensation of security when denied access to the spaces that escorted them to those feelings. In a simple sense, they were high above me and I was beneath them on the ground. The physicality of my body in relation to the people that I was paid to help became crucial in the development of almost all of my artistic viewer interactions. I realized that simply moving a body through a public space was deeply political.

On the ground–while laying under the steering column of a person’s car I was dismantling to make a key–I was low. Standing in the rain–miserable, exhausted, and waiting for me to finish–they were high above me. None of it made sense, but I dove deeply into the paradox. I was the one with knowledge and skills that could help them and they were the ones that were vulnerable and exposed. From these observations, I noticed that conceptually the physical hierarchy of the experience between myself and the customer was being inverted. I was the authority, however lowly, with dirt on my knees from crouching before the people who desperately needed my expertise. I was assuming a submissive position on my knees, but was still the person in charge. In terms of the politics that define BDSM–or Bachalard’s sphere of pure sublimation–this paradigm is sometimes described as “topping from the bottom.” Such a term describes a special and unique role that a “submissive” might assume while play-acting with a “dominant” in a BDSM relationship.

While “topping from the bottom,” the submissive retains the authority during the role play, because they set the rules and limits about what they specifically consent and submit to. This includes the use of a “safe word”–one of the major contributions the BDSM community has made to increase awareness for mutually determined play (i.e., safe, sane, consensual)–in which the submissive can stop everything that is happening by simply saying a negotiated word, “RED,” for example. In these scenarios, the submissive consents to the dominant; however the dominant often has to do a tremendous amount of labor and work to bring the fantasy to life and to keep the submissive safe.

Much of my early thinking regarding the intersection of power, locks, BDSM, and access was directly inspired by the line from The United States Declaration of Independence (US 1776) which states, “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…”4 I paraphrased this often quoted passage as “power is derived from consent” and began to dissect in minute detail what the exact mechanism by which this axiom functioned. I soon came to question whether the idea of “power” was a permanent condition that pervades the universe or if it was a social contract that we often assume to be all encompassing, but in reality is nothing more than a conscious (or unconscious) form of consent. This contextual and subjective understanding of power as a temporary condition that people consent to seemed to be further reinforced by Foucult’s writings, in which power is situated as a temporary and ever changing condition of our shared social structure that we must constantly negotiate and compromise to maintain.

As I studied the intersection of power and consent in greater detail, I began to notice a recognizable and consistent archetype of locksmithing customers and/or yoga students that I was regularly interacting with. I often found myself helping a person that was unable to create or access their own sense of safety and was looking to hire me to help them restore it or create it. However, unlike hiring a therapist, my customers were unaware of their emotional needs when hiring me as a laborer/authority in these scenarios. Admittedly, I may be projecting myself onto my customers in an unfair way and I could simply be seeing myself reflected in the people that I was tasked to help. However, regardless of how much or how little objectivity I was maintaining while observing my customers, what I saw were panicking people that didn’t know it. I saw people separated from their sense of security and unable to describe what they were experiencing. I saw people who were unaware of their bodies and didn’t know how to make themselves feel safe. When faced with the reality of a lost key, they didn’t even know they were experiencing something new. This new sensation was so foreign and ill-fitting that they itched for it to end and often took their frustrations out on me. However, I came to realize that what they were experiencing was “freedom” for the first time in their life. Being separated from our unconscious sensations of normality, regularity, and consistency creates unease. This unmediated sense of unease is freedom. And it is terrifying to people–and myself–because it turns out that true freedom is complicated, messy, and ugly. Which, in my opinion, is why we consent and relinquish power to authorities that we believe will act in our best interest.

While developing the curriculum for the first iteration of The Locksmithing Institute, I needed to come up with a working definition of “freedom” in order to contextualize why I was asking participants to do certain things. As a white, cis-gendered, hetro-sexual, male locksmith in the United States, the definition of “freedom” that seemed best reflected in my personal subjective experiences and within the observed experiences of my customers was the ability to move about the world and experience it with one’s own senses. This privileged vantage point equated freedom with “mobility” in terms of ableism, social hierarchies, social capital, and incarceration status. But regardless of those many nuanced experiences of mobility, they were facilitated by my body’s need to use its senses to experience the things around me. It turns out that this type of freedom feels like a damp, ill-fitting suit that offers little protection from the elements, nor does it conceal one’s inner nakedness. Once I started to see this complicated contextual experience of freedom–and fall out from its access or denial–I started to augment the locksmithing lessons to address these issues head on.

It was at this point that I stopped being interested in perfecting the art of locksmithing. It held little interest to me despite the fact that I was good at it. Instead, I spent all of my time trying to give up the process of picking locks or making keys. I found that, although the unease that arises from true unmediated freedom was terrible, it was better than having the illusion of freedom that is fostered by “choice,” “mobility,” lock manipulation, or by exploiting flawed engineering designs to create keys. I began to wrestle with the idea that locks do not actually bind anything if one chooses to not open them.

It occurred to me that a truly astute locksmith would know how to find the place that missing keys go when they are lost. This mythical locksmith would have lock picks constructed of inaction and would provide a customer with the opportunity to leave a door closed on their own terms as opposed to forcing it open on someone else’s. This became the fourth lesson of The Locksmithing Institute in which I attempted to help a person find their lost keys as opposed to making them a new one (see Image 6).

Although this was a fascinating exercise in futility–it turns out that I am terrible at finding keys–it is also the derivative of an incredibly privileged vantage point and does not work if one is being detained against their will. However, the spirit of the assertion lives on in our popular culture as represented by the often-repeated phrase, “One is only a prisoner if one chooses to see themselves as a prisoner.” I often thought to myself, is it possible for this trite axiom to be little more than lip service? If so, how could I put it into action?

Although this was a fascinating exercise in futility–it turns out that I am terrible at finding keys–it is also the derivative of an incredibly privileged vantage point and does not work if one is being detained against their will. However, the spirit of the assertion lives on in our popular culture as represented by the often-repeated phrase, “One is only a prisoner if one chooses to see themselves as a prisoner.” I often thought to myself, is it possible for this trite axiom to be little more than lip service? If so, how could I put it into action?

“Choosing” to be out of control is another way that the idea of “topping from the bottom” began to infiltrate my practice. Earlier, I discussed a project in which I constructed and hid inside a wheeled cabinet that was left on a New York City sidewalk. This piece began as an unofficial “part two” of Vito Acconci’s intense critique of private space, Following Piece (1969), in which he followed people from public spaces until they went into private spaces, all while being tailed by a photographic documentor. Unlike Acconci –who followed people without their knowledge or consent– I allowed people to let me follow them. They gave me unknown permission to do so, which was facilitated by their assumptions and by the unofficial rules that govern the shared use of public space in the United States.

In my piece, 9/10 (2009), I assumed the most submissive position I possibly could because I could not control where the cabinet was pushed once a person decided that they wanted it. After all, in the United States, if something is left unguarded and unclaimed in public then it is considered up for grabs. However, despite the apparent submissive position that I assumed and the apparent “abandoned” appearance of the cabinet, it was still “occupied” and I was still in charge. The people who decided to take the cabinet had no idea that I was in there nor did they know what my intentions were. This docile consent allowed me to assume a position that was so vulnerable that I usurped power back to myself. I chose to be out of control on my own terms, as opposed to submitting to someone else’s needs or desires. For me, this was a radical exploration of “topping from the bottom,” or in Bachelard’s words, I was able to sublimate while sublimating nothing.

With The Locksmithing Institute, I attempted to bring these skill sets and theories to life with lessons of subtle and not-so-subtle power exchanges between myself–“the authority”–and the participants. I would create situations in which the power would switch from them to me and vice versa. Sometimes I was vulnerable to the tools, materials, and ideas of the lesson, while at other times, the participants would be exposed. Sometimes my body would be low, and theirs would be high. I would be in control, but exposed, and they would be out of control, but safe. For example, I taught people how to cut the chain that binds handcuffs together with an electric grinder as opposed to teaching them how to pick the lock (see Image 9). I knelt before them without safety gear and guided their wrists over the grinder. They remained standing–shrouded and anonymous–in protective gear, safe from the experience, but restrained by the handcuffs.

In another iteration of this project, I first taught people on a New York City sidewalk how to pick the locks of standard handcuffs. I then gave participants the option of sitting with their wrists zip-tied together for five minutes while isolated in a black hood. In the first part, they actively chose to fight against the lock by picking it. In the second part, they actively chose to not pick the lock by sitting with the sensation. I then asked them to compare and contrast the two sensations (see Image 10).

Although I have been exploring these motifs since 2005, the most recent example of this gesture was done in 2019. I erected a large white wall in the gallery of a Southern Californian art organization called the Grand Central Art Center (see Image 11). This wall separated their main gallery from the entrance. In order to enter the gallery and see the art exhibition, I first had to teach participants to manipulate and open a secret door hidden within the wall. We were both on our knees.

In all of these projects, I hoped to create a more egalitarian, subtle–while at the same time–very complicated scenario. These scenarios looked innocuous and playful on a surface level, but upon inspection were layered with complicated power shifts of human bodies moving through public spaces while performing actions with symbolic overtones. The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu created a term called “social capital” which I have found very helpful in the creation of my viewer interactions. Social capital refers to the non-material resources possessed by educated individuals from upper class families that are not based on literal money. Social capital describes how a person’s physical deportment and composure while maneuvering through the public sphere is one of the crucial–and hidden–ways that wealthy individuals navigate upward mobility. Some examples of this are: a person’s choice of words, speech accent, social graces, physical composure, eye gaze, and “sense of ease.”

These are the forms of “wealth” that are silently passed down to children who are born into the upper echelons of capitalist cultures. This “sense of ease” is often referred to as noblesse oblige and is very difficult–if not almost impossible–to learn consciously if one is not born into the privilege of wealth and power. Bourdieu insists that this type of knowledge is hidden within the structure of our educational systems, which on a surface level are presented as “merit-based” and “democratic.” A person will not be directly “taught” social capital while attending a top tier elementary school, but that person will “learn” it because they have been educated within that context. This echoes Foucult’s observations about how institutions conceal power under the guise of social norms and the natural order. Navigating the complicated bureaucracies and social networks that decide who gets to access the best jobs and resources becomes very difficult for a person that does not know how to say the “right” words, in the “right” way, to the “right” person, at the “right” time. I detest this notion–even if Bourdieu’s assessment is right, and he is right–and prefer to show people the back door whenever possible. Sometimes I needed to get down on my knees to show people how to do that.