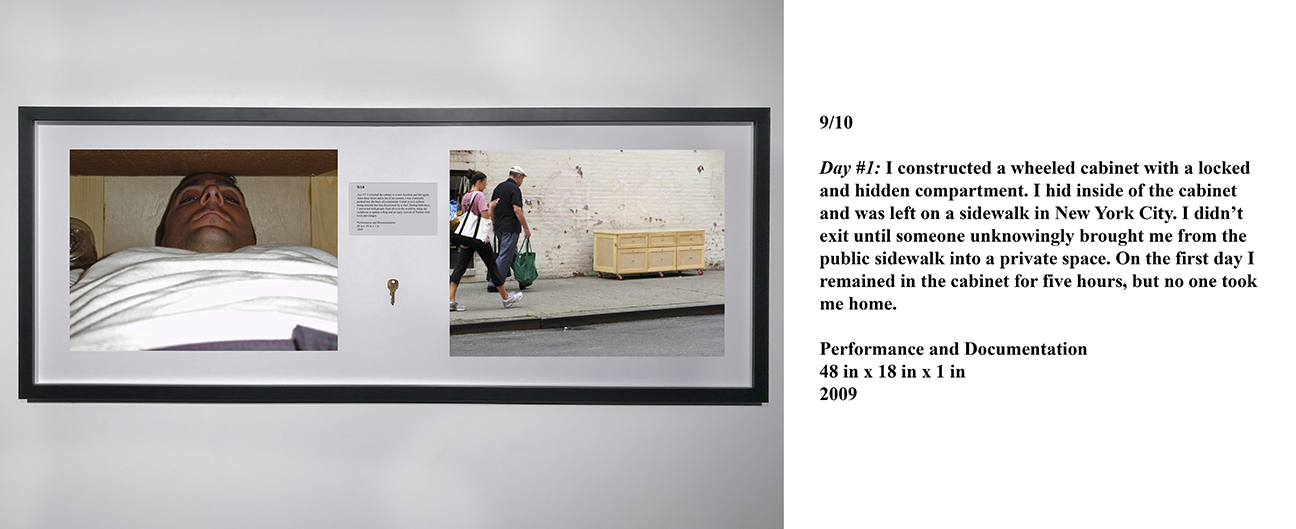

9/10: Day #1, New York City, September, 2008

A cabinet will be constructed and left on a sidewalk. I will be hidden inside and not reveal myself until someone assumes possession and brings the cabinet from the public space to a private space. To read in detail about this experience please follow this link to my blog: http://lucasmurgida.blogspot.com/2008/ and also the Twitter feed that I was updating during the experience: https://twitter.com/lucasmurgida. As with the other pieces in the Yoga Teacher Series, in this project I am examining one of the five senses. 9/10 revolves around our sense of sight and perception.

Often the city seems to be ours alone to experience and we assume that it is in turn ours for the taking. This sensibility is made evident in the U.S. by the often-quoted phrase, “Possession is 9/10 of the law.” This means that the person who is not in possession of an item must prove that it is rightfully theirs. As each of us navigates the city we perceive the occurrences that we come into contact with to be unique to ourselves. This seems rational as each person observes events from a specific vantage point. These observations become confused by the witness because s/he interprets those public experiences through the filter of the their personal histories. For example, one person sees an event to be a hostile confrontation while another will see it is a playful exchange. As we experience the city we lay claim to our interpretations and often make the assumption that things are as they appear to us to be. The burden of proof then rests upon another to prove that this is not so. Nowhere is this more evident than when something that may be private property is placed in a public space. A person is not sure how to look at the object at first, but will usually fall back on the golden rule of U.S. culture (finders keepers, losers weepers) and claim it to be theirs. I am hoping to subvert the “finder’s” personal space by claiming it to be my own public space. As with the other pieces in the Yoga Teacher Series, in this project I am examining one of the five sense. 9/10 revolves around our sense of sight.

This outdoor intervention will be in place west of the Center for Architecture and south of Washington Square Park in New York City on Saturday, September 13th, from noon onward as part of The Conflux Festival.

Follow this address to learn more about the festival: www.confluxfestival.org/conflux2008/910/

Notes from Day #1:

This piece began as an unofficial “part two” of Vito Acconci’s intense critique of private space, Following Piece (1969), in which he followed people from public spaces until they went into private spaces, all while being tailed by a photographic documentor. Unlike Acconci –who followed people without their knowledge or consent– I allowed people to let me follow them. They gave me unknown permission to do so, which was facilitated by their assumptions and by the unofficial rules that govern the shared use of public space in the United States.

My interest in this topic began many years ago –before I knew anything about locks, yoga, power-politics, or BDSM– when I read the book The Poetics of Space (1958) by Gaston Bachelard. In its pages, I dove deep into all the things I found magical about furniture, cabinets, corners, and cellars. As Bachelard asserts in the book, these are the spaces in which a child first learns to dream. The book was very inspiring and it is still something I skim through every so often when I want to dream. In the book’s introduction, Bachelard talks about a type of psychoanalytical investigation in which, “…we are able to isolate a sphere of pure sublimation; of a sublimation which sublimates nothing, which is relieved of the burden of passion, and freed from the pressure of desire.” I didn’t understand the quote at the time, but I kept thinking about it. Years later, while I was trying to help people during locksmithing jobs, it kept popping into my head as I’d be physically kneeling on the ground trying to open locks for customers who –while standing above me– were mentally incapable of creating a sensation of security when denied access to the spaces that escorted them to those feelings. In a simple sense, they were high above me and I was beneath them on the ground. The physicality of my body in relation to the people that I was paid to help became crucial in the development of almost all of my artistic viewer interactions. I realized that simply moving a body through a public space was deeply political.

In 9/10, I assumed the most submissive position I possibly could because I could not control where the cabinet was pushed once a person decided that they wanted it. After all, in the United States, if something is left unguarded and unclaimed in public then it is considered up for grabs. However, despite the apparent submissive position that I assumed and the apparent “abandoned” appearance of the cabinet, it was still “occupied” and I was still in charge. The people who decided to take the cabinet had no idea that I was in there nor did they know what my intentions were. This docile consent allowed me to assume a position that was so vulnerable that I usurped power back to myself. I chose to be out of control on my own terms, as opposed to submitting to someone else’s needs or desires. For me, this was a radical exploration of “topping from the bottom,” or in Bachelard’s words, I was able to sublimate while sublimating nothing.

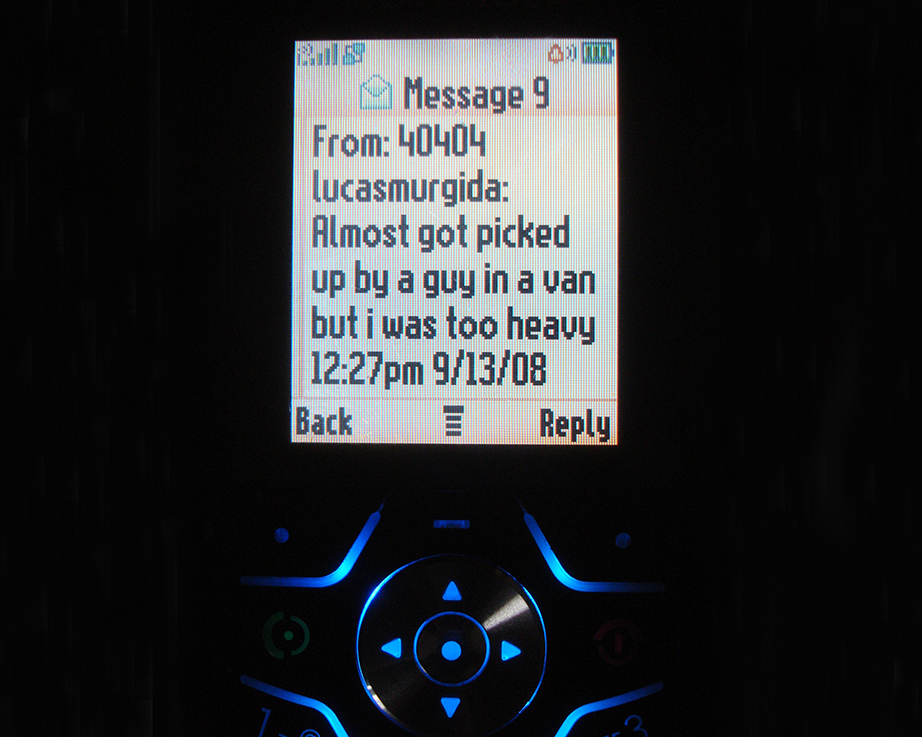

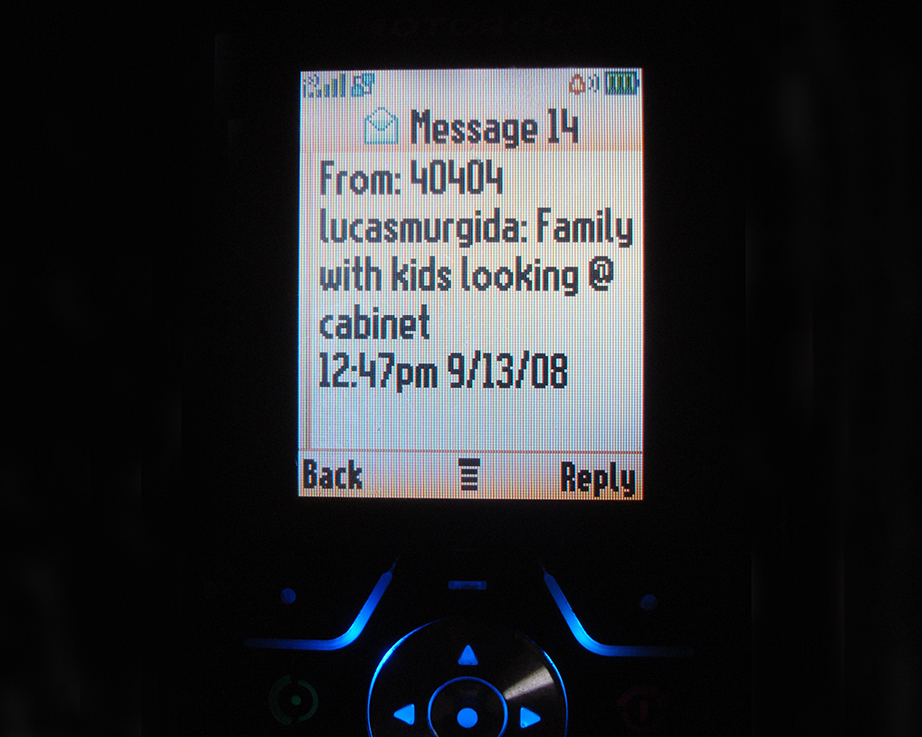

There were four different audiences that I was trying to engage with this work. The first were the people monitoring my progress online via my text messages and photos. I received text messages from people in Boston, San Francisco, New York, and London. It was interesting and demanding to try to describe what I was experiencing and feeling while this process was going on. It was also very intense for some of the people monitoring as well. My brother commented that while I was locked inside my box the people monitoring my progress were locked in their own box of a different sort, as each of us were equally out of control of the situation. Mine was a box of wood while theirs were computer screens or cell phones. The next tier in the audience was the people that came to the Conflux festival and went out to try to find my cabinet in the city. I didn’t give a specific location so they were required to explore and re-examine the city in a different way in order to find me. My hope was that they would have a similar experience as I did when I was looking for the right spot to leave the cabinet. Over the course of several days I wandered around the neighborhood near the Center for Architecture until I happened upon the spot that would satisfy my needs for the piece. The third segment of the audience were the people that had no idea that I was inside the cabinet and were simply interested in bringing the piece of furniture to their home. I had surrendered the control of my movements to them and in turn was able to listen and observe their interactions with the cabinet. As with my last few pieces, I surrendered my power to them and appeared to assume a very submissive position. However I would argue that it was I that was in fact in control of the situation as these people were unaware of my presence or my intentions. The last audience member was myself, observing and trying to record my reactions to the situation.

I stated briefly that this experience was intense for the people monitoring me via the web. It was also intense for me as well and I attempted to be as candid as possible about what I was feeling during the experience. Interestingly, when it was over, I felt un-phased by it. I was interacting with people almost right away and was busy analyzing what went right and what went wrong. I was disoriented, hot, sweaty, and thirsty when I exited the cabinet both days, however, I recovered from this rather quickly. I kept waiting for the other shoe to drop, and for some sort of intense emotional reaction to arise, but it never came while I was in New York. Two days later when I was back in San Francisco it hit me hard. For four days I had nightmares, restless sleep, anxiety, and depression. While I was experiencing this aftermath I knew that it was the by-product of the piece however this knowledge did not temper the emotional roller coaster. I still wake up hot and sweaty and, those of you that have ever lived in San Francisco know that the weather is rarely warm enough to produce this sort of heat in a person’s body while they are sleeping.

I would like to offer a special thanks to Sara Dierck for once again documenting my life with her photography as well as putting up with the stress that comes with witnessing difficult works of art.