The Locksmithing Institute, February 2005-present

Since 1999 I have been using my jobs and employment as research to inform my art practice. I have worked professionally in roles such as a cabinet maker, fine-dining busboy, production worker for bondage and fetish films, and yoga teacher, and I mined these job skills and situations as a platform from which to produce artistic work. This includes my best-known body of work, The Locksmithing Institute (February 2005-present), produced from the time that I spent working as a professional locksmith from 2002-2011.

Working a night shift, 2004

The artwork that arises as the result of my different employment/research projects changes, but my time spent working as a locksmith was the influence for a conceptual project called The Locksmithing Institute. This “school” traveled to different public places and aimed to teach anyone interested concepts and skills related to locksmithing. Initially, the lessons were a derivative of the physical activities that I executed while working as a locksmith, such as picking locks or making keys. Each class consisted of both a mechanical lesson–for instance, “How to pick a lock”–and also an embedded conceptual lesson. For example, in order to pick a lock, a person needs to use “pressure” and “manipulation” in order to coax the device open. It is not without coincidence that those words–with powerful cultural histories–are used in conjunction with that lockpicking process. It was up to participants whether they wanted to discuss this connection between theory and practice or just to learn how to pick a lock. I would develop the lessons in four or five parts and let participants dictate how much or how little they got out of the experience. This multi-tiered approach allowed me to cater to children, adults, art-experts, and art-novices simultaneously in a seamless fashion.

First class of The Locksmithing Institute, February, 2005

Mobilizing these theories and attempting to put them into the hands of The Locksmithing Institute participants as a practice that they could utilize in their daily lives became the ultimate drive of my research. A process such as this is sometimes described as a marriage between “theory” and “practice.” However, over the years I have come to define this dyad in a different way. Instead, I see this dynamic as a combination of “theory” with “skill-sets.” And–if approached from the right angle–this union of theory and skill-sets can create an “art practice.” Although I used this process to specifically create The Locksmithing Institute, it could be implemented to explore any skill set from washing dishes to automotive transmission repair. The possibilities are limitless and anyone can do it.

Lesson #4, June, 2006

In 2006, after doing three different lessons, the classes quickly moved away from being about anything directly related to locks or keys and began to focus on the psychological conditions that I noticed in the people that I was hired to help during my daily locksmithing jobs. I shifted the focus of the classes away from practice and more towards a theoretical analysis that centered around the following question that I authored: What happens to people when they become separated from places that make them feel safe and secure like their home or their car?

From this point forward, the lessons of The Locksmithing Institute focused on escorting participants into situations that gave them the opportunity to change their relationships to keys by fostering an inner sense of safety and security. This allowed them to create their own feelings of security without the mediation of keys to facilitate the experience. To do so, I broadened my definition of “the key” to become largely symbolic, encompassing people, places, things, ideas, as well as traditional physical keys. A key became anything that allows a person to enter or exit a physical, intellectual, or emotional space. I made situations that allowed people the opportunity to experience the creation of their own sense of security without a key to trigger their response. To do this, I started moving people into and out of different confined situations, while asking them to compare the sensations that arose while feeling “stuck” and then “unstuck.” For instance, in 2006, I asked people at a public park in Frey Bentos, Uruguay to purposely lose their keys as an act of agency as opposed to carelessness or trauma. I then brought their keys back to the United States and “lost” them on their behalf.

Lesson #6, 2006-7

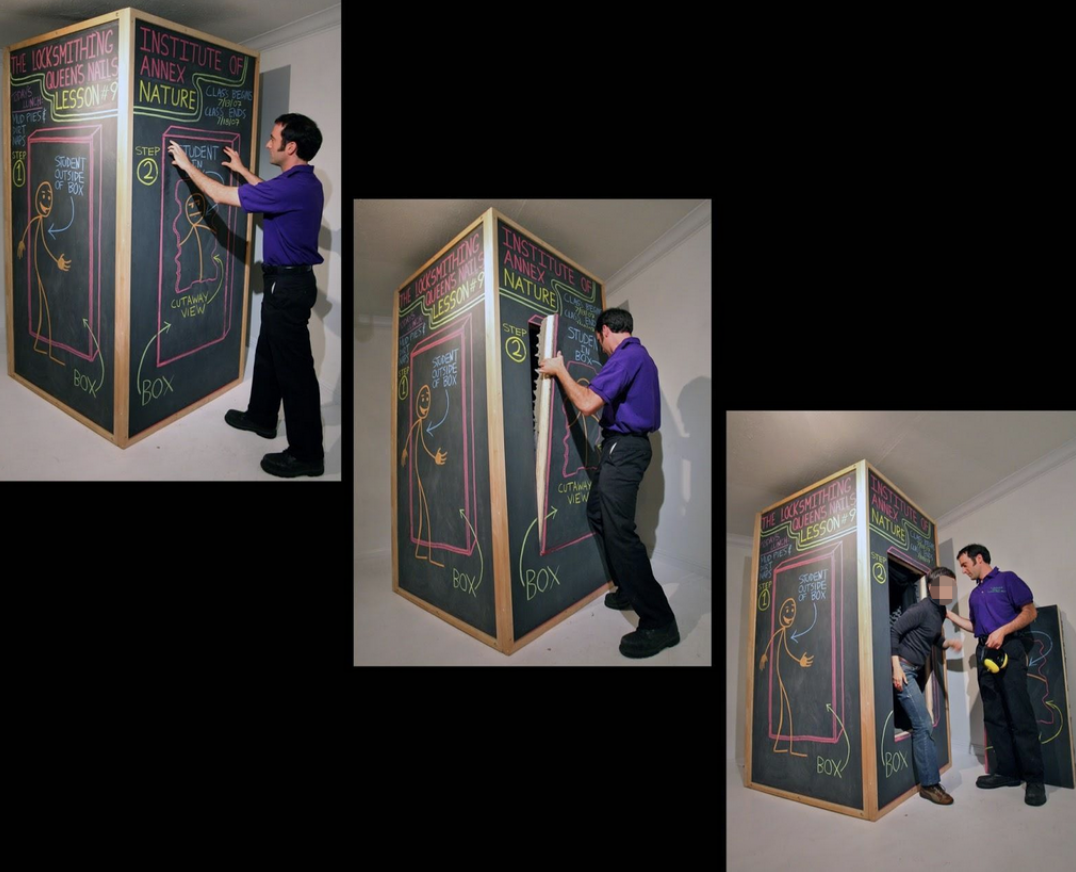

In another iteration of this project, I first taught people on a New York City sidewalk how to pick the locks of standard handcuffs. I then gave participants the option of sitting with their wrists zip-tied together for five minutes while isolated in a black hood. In the first part, they actively chose to fight against the lock by picking it. In the second part, they actively chose to not pick the lock by sitting with the sensation. I then asked them to compare and contrast the two sensations. In 2007, I constructed another class in which I invited individual participants to take turns sitting for five minutes inside of a noise-canceling isolation chamber made from chalkboards. While one person was inside, other participants waited outside for their own turn in the chamber and joined me in a discussion about how we each construct our personal sense of security and mental fortitude.

Lesson #9, 2007

After seeing this exhibition, artist and educator Jennifer Locke initiated a conversation with me regarding the embedded power dynamics that I was mobilizing in my lessons. It was from this conversation that I really began to make the connection between what I was studying as a locksmith and the relationships that are constructed and implemented between dominants and submissives in BDSM relationships. Much of my initial thinking regarding locksmithing had been inspired by Michel Foucault’s seminal work, Discipline and Punish (1975). Like many young thinkers, when I first read the book as an undergraduate, I was most inspired by his analysis of the systematic observational models that have been implemented within all of our institutions –schools, hospitals, prisons– to fluidly maintain power. Years later, after my conversation with Locke, I realized that although those initial ideas were powerful eye-openers for me, what I was actually most drawn to was how these institutions conceal power. In Foucault’s own words, “The punishment must proceed from the crime; the law must appear to be a necessity of things, and power must act while concealing itself beneath the gentle force of nature.” It occurred to me that the ability to make a power structure–which in my opinion is a temporary condition of our shared social structure–appear as if it was a permanent condition that has always always existed in the natural world, could be an incredibly powerful tool if wrenched from the hands of the dominant discourse.

From this realization, a second arc of research emerged in my art practice. In 2002 –simultaneously with locksmithing– I also started to practice yoga. I did this to compare how we lock and guard our spaces, compared to how we lock and guard our bodies. As my time working as a locksmith drew to a close, I transitioned into working as a yoga teacher. The politics of BDSM only became increasingly apparent while I was teaching yoga and were reflected in the art projects that I made about this employment/research. I found the intense power dynamic in a yoga classroom to be very unnerving. Helping people into and out of painful and challenging situations created a power vacuum, which while acting as “the authority” struck me as problematic. This is ironic because I have no problem going to a class as a student and working with a teacher I really trust. In the end, I do not think I was ready for the responsibility and only worked as an instructor for a couple of years. The artwork that came out of this experience focused on intense power exchanges between myself and–mostly–unaware participants.

Much of my early thinking regarding the intersection of power, locks, BDSM, and access was directly inspired by the line from The United States Declaration of Independence (US 1776) which states, “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…” I paraphrased this often quoted passage as “power is derived from consent” and began to dissect in minute detail what the exact mechanism by which this axiom functioned. I soon came to question whether the idea of “power” was a permanent condition that pervades the universe or if it was a social contract that we often assume to be all encompassing, but in reality is nothing more than a conscious (or unconscious) form of consent. This contextual and subjective understanding of power as a temporary condition that people consent to seemed to be further reinforced by Foucult’s writings, in which power is situated as a temporary and ever changing condition of our shared social structure that we must constantly negotiate and compromise to maintain.

As I studied the intersection of power and consent in greater detail, I began to notice a recognizable and consistent archetype of locksmithing customers and/or yoga students that I was regularly interacting with. I often found myself helping a person that was unable to create or access their own sense of safety and was looking to hire me to help them restore it or create it. However, unlike hiring a therapist, my customers were unaware of their emotional needs when hiring me as a laborer/authority in these scenarios. Admittedly, I may be projecting myself onto my customers in an unfair way and I could simply be seeing myself reflected in the people that I was tasked to help. However, regardless of how much or how little objectivity I was maintaining while observing my customers, what I saw were panicking people that didn’t know it. I saw people separated from their sense of security and unable to describe what they were experiencing. I saw people who were unaware of their bodies and didn’t know how to make themselves feel safe. When faced with the reality of a lost key, they didn’t even know they were experiencing something new. This new sensation was so foreign and ill-fitting that they itched for it to end and often took their frustrations out on me. However, I came to realize that what they were experiencing was “freedom” for the first time in their life. Being separated from our unconscious sensations of normality, regularity, and consistency creates unease. This unmediated sense of unease is freedom. And it is terrifying to people–and myself–because it turns out that true freedom is complicated, messy, and ugly. Which, in my opinion, is why we consent and relinquish power to authorities that we believe will act in our best interest.

While developing the curriculum for the first iteration of The Locksmithing Institute, I needed to come up with a working definition of “freedom” in order to contextualize why I was asking participants to do certain things. As a white, cis-gendered, hetro-sexual, male locksmith in the United States, the definition of “freedom” that seemed best reflected in my personal subjective experiences and within the observed experiences of my customers was the ability to move about the world and experience it with one’s own senses. This privileged vantage point equated freedom with “mobility” in terms of ableism, social hierarchies, social capital, and incarceration status. But regardless of those many nuanced experiences of mobility, they were facilitated by my body’s need to use its senses to experience the things around me. It turns out that this type of freedom feels like a damp, ill-fitting suit that offers little protection from the elements, nor does it conceal one’s inner nakedness. Once I started to see this complicated contextual experience of freedom–and fall out from its access or denial–I started to augment the locksmithing lessons to address these issues head on.

It was at this point that I stopped being interested in perfecting the art of locksmithing. It held little interest to me despite the fact that I was good at it. Instead, I spent all of my time trying to give up the process of picking locks or making keys. I found that, although the unease that arises from true unmediated freedom was terrible, it was better than having the illusion of freedom that is fostered by “choice,” “mobility,” lock manipulation, or by exploiting flawed engineering designs to create keys. I began to wrestle with the idea that locks do not actually bind anything if one chooses to not open them.

It occurred to me that a truly astute locksmith would know how to find the place that missing keys go when they are lost. This mythical locksmith would have lock picks constructed of inaction and would provide a customer with the opportunity to leave a door closed on their own terms as opposed to forcing it open on someone else’s. This became the fourth lesson of The Locksmithing Institute in which I attempted to help a person find their lost keys as opposed to making them a new one.

Those are some of key elements that have informed this body of work. Detailed examples of each project can be found on my website. Since 2005, The Locksmithing Institute has gone through many different iterations and from March 2018 to September 2019 I had the opportunity to share this work in the city of Santa Ana, CA as a long term artist in residence for the Grand Central Art Center which is part of California State University, Fullerton, funded through a grant from the Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts. Over the course of a year and a half, I constructed five unique installations and viewer interactions to engage the community of Santa Ana during their very busy monthly art-walks.

Working a night shift, 2004

Written in 2007:

In October 2002, when I began working as a locksmith I also began to practice yoga. I did this to compare the similarities between how culturally we guard and lock our spaces with how we physically lock and guard our bodies. In February 2005 I began to make the artwork that came as the result of these two bodies of research. What follows is the culmination of the first 9 lessons of The Locksmithing Institute. I freely admit that although I took on the guise of a teacher for these performance pieces, that I was in fact the student. This lesson plan has been inspired by the interactions that I have had with hundreds of people on a day-to-day basis as a locksmith and from my basic understanding of yogic thought.

This is what I have come to understand:

Often a lock is viewed as a device that deflects energy. It is presumed that a lock pushes away the attempt of a person who is trying to break or pick it. However a lock does not in fact inhibit the path of a forced entry. In actuality it takes that energy, absorbs it, spreads it out, and thusly, renders it impotent. Indeed locks are passive vessels for the absorption of energy. Locks are a creation of people. People are of course clever but hardly original. We have survived by observing that which surrounds us and adapting those disparate materials and ideas together to serve a new purpose. The question then becomes: What was it that people observed when they were first inspired to create a lock? I submit that it was themselves. This observation implies that a people are bound entities and that their relationship to that which surrounds them is locked as well. This also implies the universe is in a bound or locked state. This is not the case. The universe is one open, fluid, mechanical, natural, and spiritual entity and as a part of this universe the same must be said of humans. Viewing ourselves and all that surrounds us as locked, bound, or hidden is quite possibly the root of all suffering.

To understand this point better consider for a moment the opposite of what being in a bound or locked state implies by considering what it means to be free. If I ask myself, “What does it mean to be free?” the implication is that I am confused about freedom. I then attempt to use language to discuss this notion as a polarity. I am free. I am not free. I can ask myself what sensations arise in considering both. Further, by using language I can dissect my relationship to the idea of being free, however, this is not a productive way to understand this idea as it will inevitably lead to greater and more profound confusion and or suffering.

Image that we find a remote island in the Pacific Ocean that has been isolated from the world. We attempt to communicate with the inhabitants of the island and as time goes on we notice that there are some major differences between our two languages, most notably that they have no word for freedom. If one lives in a society where there is an open and fluid sense of movement between all things a notion of “being free” would make no sense. It would be just something that “is”. It could be said that the notion of being free is something that has been created to exert control over people. It is the manipulated quantification of an unalienable right. As a king I say to a peasant, “You better be good or I will put you and jail and then you won’t be free.” We associate being free with the ability to move about our world and experience it with our senses. In my opinion this is not freedom. In fact this is the jail.

What I have found in the four years that I have been locksmithing is that locks do not confine us to certain sections of space and deny our access to others. It would seem that only our perception is capable of achieving this incredible feat of shackling. I suppose the point is (and I am certainly not the first to discover this) that we are only captive if we choose to perceive ourselves as captive. Considering these things, one might ask how it is possible to navigate the world in a different way. To answer this question let us take a moment to examine keys.

It is first necessary to broaden the definition of keys. Anything that allows us to enter or exit a space – be it physical or mental – is a key. All of the people, places, and things in our life are keys. Each allows us to enter or exit certain physical and cognitive spaces. When viewed this way, the universe becomes one immense haunted space and all things within it act as triggers to alter our consciousness. This haunted condition allows us to bounce between many different times, places, and emotions without even realizing it.

The word haunted itself doesn’t mean anything. It is instead a sensation that arises due to the perpetual state of occupation that exists everywhere. Our physical keys mirror this paradigm. As they rattle in our pocket our state of occupation becomes amplified. They are not all they seem to be. Keys are supposed to unlock our feelings of safety and security, but on the contrary, they are our shackle to certain things, ideas, or people. We are supposed to be free people, but we are not. Our keys maintain our detention by making us feel that we are safe and that we can move about our world with freedom. We leave our home and lock the door only to unlock the door to our car and then lock ourselves in. We travel to our job, unlock the door and place ourselves in another cell. We feel safe in these prisons. When we misbehave most will find some overt or covert way to punish themselves. In our present haunted and occupied condition we are our own jailor and we have been fooled into thinking that our keys (be they physical or mental) are the proof of our supposed freedom. There is no need for a prison for the majority of the people as our pockets insure that we will remain passive. We simply need to be periodically reminded that we are in danger so that we keep our cells locked tight.

Due to this situation, when a person loses their keys they often work themselves into a panicked state. This sense of crisis amplifies when the particular lost key happens to unlock someplace that is associated with the person’s sense of security such as their home or car. This panicked state implies that one’s sense of safety and security exists outside of themselves. It would seem that when the keys are lost it forces people to face themselves as they are. Our perception of the world is very delicate. The keys maintain the balance for us. The irony is when the keys are safely on their ring they make it possible for us to be lost to ourselves. When they are lost (in spite of the panic that one may feel) we are forced to provide our own feelings of safety and security. Because of this our keys have been metaphorically transformed into the sensations that we associate with all of the forced connections we have with people, places, and ideas that we externally associate with our notions of ourselves. Meaning simply that on a moment-to-moment basis I am my sensations as I have no clear conception of myself separate from my desires, regrets, or fantasies.

A clear way to understand this point is through yogic philosophy. The universe is like a mirror. As our senses interact with it the universe reflects back to us a glimpse of our”self”.The problem is, as we gather information our desires, feelings, attachments, or “keys” refract those sensations because we have transformed the universe into this haunted state. Like a funhouse mirror the reflection is tainted and therefore does not accurately show us what we are. At its core, life is simply the opportunity to have sensations. These sensations, though a product of life (and an incredible gift) do not represent the totality of what we are. The inability to separate our sensations (keys) from the way in which we interpret the information that we receive through our senses has been merciless to countless beings since the dawn of consciousness.

In light of all these things, it seems possible that our keys, be they mental or physical, do not exist at all. And this lack of existence is what enables them to embody such an incredible, otherworldly power. Our keys have taken on a paranormal identity just as our world has been transformed into a haunted state. Simply, if the world is the haunted house then our keys are the ghosts. We each live with this constant paranormal presence. A ghost is not something that leaves one space and pops into view in another. Nor is it something that exists in between two realms. Ghosts are not sheets, nor ideas, nor traces, nor any manner of philosophical quandary or folk tale. Further, the misconception that a ghost is something we notice when it appears before us not accurate. In actuality their presence is only noticed when they disappear. And only upon their vanishing do we appreciate that they were there. Only when they are gone do we panic. And, only when they are gone does one truly fear that which they have created for themselves and the ghost they permit to reside in their pocket.

For some time I thought that a great locksmith would be able to find the place that keys go when they are missing. I have realized this is impossible because, as discussed, they do not exist. I then thought that in order to gain freedom we must lose our keys of our own free will. However, forcing this liberation to occur is not necessary either. Despite the fact that we are desperately connected to our keys, we lose them anyway. It would seem that there exists somewhere in each person the knowledge of how to set ourselves free. When we accidentally lose our keys we move towards this liberated state without any effort at all. This natural, uninhibited movement towards freedom is the final proof that our natural state is not confined, suffering, nor bound. The only work that must be done is to extinguish fear so when the day comes that the keys disappear there is no panic. From there, we need only experience existence without them acting as our filter. And this ghostless, filterless, keyless state is freedom. Unfortunately, when this freedom is found there is no revel or bliss that will occur. This state is the baseline; it is our natural, balanced condition. There are no words that I can use from this point forward to describe what this existence might be like. In my opinion, this is where language ends.