The Service Series consists of a set of diptychs that I created to deconstruct the uniform that I was wearing in many of my performance pieces from 1999-2004 that were inspired by my employment and research as a busy boy in fine dining restaurants. There are seven diptychs in this series that deconstruct and recontextualize the usage and purpose of my black shoes, black bag, black socks, black pants, black belt, white shirt and black tie. More information below:

When I arrived in San Francisco in the fall of 1999 I took a job in a fine dining restaurant as a busboy. Prior to my arrival in San Francisco, I had been working as a cabinetmaker in a small furniture factory in Boston for three years. While in San Francisco, I was going to school full time during the day so I was unable to find a cabinet shop that would allow me to work nights. Thus, I started working in restaurants.

Busboy in San Francisco, 2000

My first body of work dealt with furniture and cabinets and can be seen in my Cabinet Maker Series. However, my employment and research as a busboy slowly started to infiltrate my art pieces. I began to either perform or interact with people postured as a service person, busboy, or attendant. I was usually a silent, sculptural element in those installations, interventions, or performances whose job was to perform a task.

The Service Series officially began in November 2000 when Tony Labat brought a group of students to Cuba to participate in the Havana Biennial Art Fair. For my project, I convinced a local family owned restaurant to let me work for them for a couple of nights as a busboy. My goal was to earn one United States Dollar, which was the preferred form of currency used by Cubans at the time. Over the course of two days, I worked for about 18 hours and earned 19 pesos. At the time there were 21 Cuban Pesos in 1 U.S. Dollar. I didn’t officially achieve my “goal” but the 18 hours that I spent with the community at that restaurant changed my life forever.

Busboy in Cuba, 2000

The 19 Cuban Pesos that I Earned, 2000

The pieces that comprise The Service Series deconstruct the persona that I was adopting during my those performance pieces by investigating the uniform that I would wear, consisting of: black shoes, black socks, black pants, black belt, white shirt, black tie and (sometimes) black bag. I still occasionally adopt the busboy persona when I perform or do viewer interactions.

Performing my project Lunch in my Busboy Uniform, 2001

Performing in my Busboy Uniform, 2001

The documentation of The Service Series was informed by one of the first conceptual motifs that I studied in earnest: the use of tools outside of their intended purposes. My fascination with this concept began when I was 17 years old after reading Paul Auster’s short story, City of Glass (1985), for the first time. There is a character in the story that wanders around New York City collecting and cataloging broken items, such as umbrellas, documenting how they are broken, and giving them new names. The character’s assertion is that an object is defined by its use, and if the object is broken and can no longer execute its function, then it can no longer be considered an “umbrella.” This idea stuck in my young mind because at that point in my life objects and ideas had “purpose.” It seems unlikely that the idea of “purpose” is a permanent condition that applies to the entire universe; however, at that young age, it seemed to describe the affairs of humans and the unseen social contracts that govern how we have agreed to experience the world. Years later, when I was an undergraduate, I was shown documentation of Joseph Kosuth’s seminal work One and Three Chairs (1965).

One and Three Chairs, Joseph Kosuth, 1965

This piece changed the way I thought about my practice and also the documentation of art in general. In the piece, Kosuth presents three artistic gestures in close proximity to one another: a physical chair (an object), a photograph of the same chair (a picture of the object), and a printed dictionary description of the word “chair” (the definition of the object). This piece is still very important to me; however, I have always had a problem with it. In my opinion, Kosuth neglected to display a chair’s fourth and most important descriptive characteristic: its use in action, its purpose. In my reductionist brain, a chair is only a chair if it is used and sat upon. I then asked myself what happens if a chair is used in a way that is outside of its standard definition and purpose? Is it still a chair? For me–and countless other artists–this led to an explosion of possibilities to create new meanings by subverting the accepted purpose of an object.

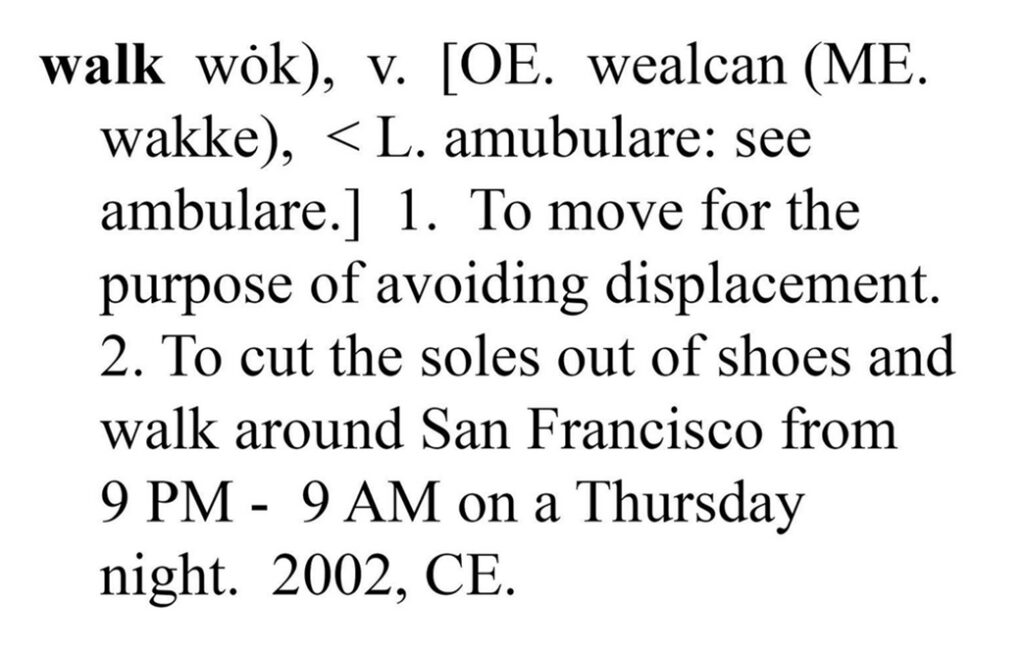

To explicate this point I did a series in which I took the clothes that I would wear while working as a busboy in fine dining restaurants and did public performative actions in which each article of clothing was used or recontextualized outside of its intended purpose. This new use would have a corresponding effect on my body. Sometimes I would modify each article of clothing and other times I left them unmodified. However, the context and usage of the article of clothing would have subtle and not-so-subtle effects on my body. For example, I cut the soles out of the bottom of my shoes and walked around San Francisco for 12 hours. Almost no one noticed that my shoes had no soles and certainly no one knew that I was attempting to make art. To show this work in its completed form, I displayed a formal photograph of the shoes set against a white background and juxtaposed it with a photograph of my dirty and damaged feet taken immediately after I finished my walk. I placed the physical shoes I walked in between the two photographs, along with a small piece of text that looked like a dictionary definition of the word “walk,” but was instead re-contextualized the photographs, object, and action in order to not only create a new definition but to make a new contextual meaning.