When I arrived in San Francisco in the fall of 1999 I took a job in a fine dining restaurant as a busboy. Prior to my arrival in San Francisco, I had been working as a cabinetmaker in a small furniture factory in Boston for three years. While in San Francisco, I was going to school full time during the day so I was unable to find a cabinet shop that would allow me to work nights. Thus, I started working in restaurants.

My first body of work dealt with furniture and cabinets and can be seen in my Cabinet Maker Series. However, my employment and research as a busboy slowly started to infiltrate my art pieces. I began to either perform or interact with people postured as a service person, busboy, or attendant. I was usually a silent, sculptural element in those installations, interventions, or performances whose job was to perform a task.

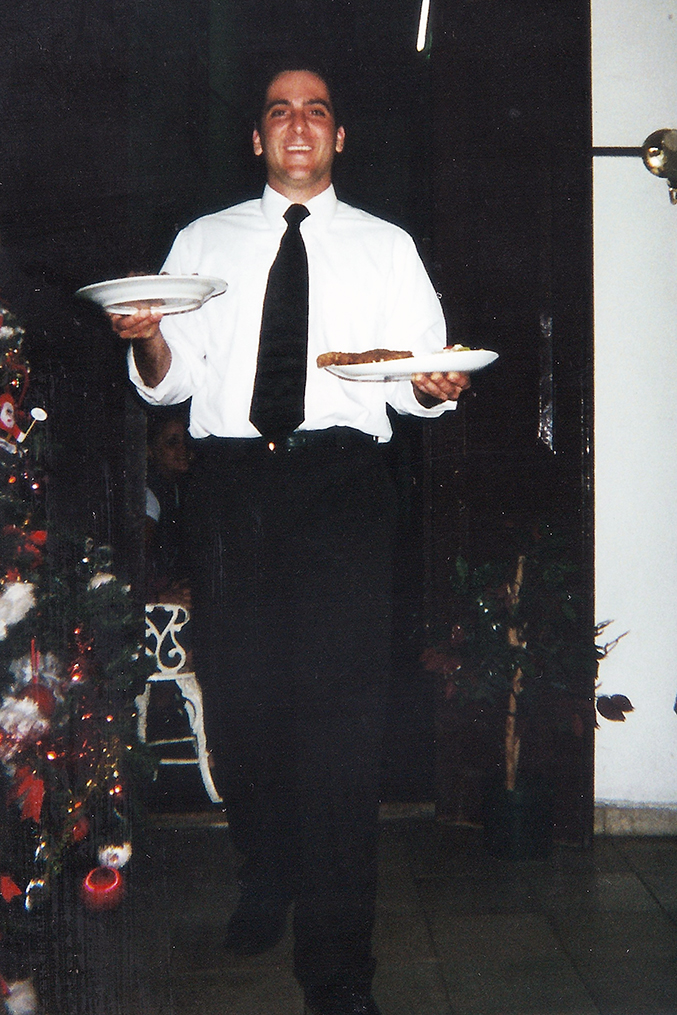

Performing my project Lunch in my Busboy Uniform, 2001

My second body of work –The Service Series– officially began in November 2000 when Tony Labat brought a group of students to Cuba to participate in the Havana Biennial Art Fair. For my project, I convinced a local family owned restaurant to let me work for them for a couple of nights as a busboy. My goal was to earn one United States Dollar, which was the preferred form of currency used by Cubans at the time. Over the course of two days, I worked for about 19 hours and earned 19 pesos. At the time there were 21 Cuban Pesos in 1 U.S. Dollar. I didn’t officially achieve my “goal” but the 19 hours that I spent with the community at that restaurant changed my life forever. Below is what I wrote about the experience right after I completed the project in 2000. At the time, I was 24 years old and still had a lot of learning and growing to do:

Written November, 2000:

The decision to do this project in Cuba was inspired by the many people from Mexico, Central America, and South America that I had worked with in my life. I have developed a great deal of respect for them because they traveled very far and –at times– risked their lives to come to the United States. Though some were coming in search of safety and freedom, I have found that many came because financially there were no opportunities in their home countries. Many worked here and sent money home to their families to build houses, buy food, of –among other things– for their families to save money and make the trip to the United States themselves. What struck me about this was that the central reason for coming was the United States dollar. But what began to sicken me was that it became apparent that the reason why their countries were so poor and they were forced to leave their homes was the influence that the United States dollar levied on their countries.

Before I went to Cuba, I was working in a restaurant as a busboy and had been saving my cash tips and earnings to pay for this special trip. I decided that in Cuba I wanted to try to find a job in a restaurant as a busboy. My goal was to earn one United States dollar. When I arrived in Havana, one of the first restaurants that my group ate at was a small family owned “Paladar” which is the general name for the restaurants that Fidel Castro has allowed families to run out of their apartments or houses to serve tourists. After dining, I told one of the waitresses –named Laticia– that I was a United States artist and that I also worked as a busboy. I asked her if I could come in and work for one night without pay. Explaining as best as I could in my broken Spanish, I relayed to her that I considered this part of my work as an artist and took it very seriously. She agreed and I told her that I would come by in a week.

Clearing plates when my group ate at the “Paladar”

A week later I returned to see if the “job” was still available and if so, what day I should come in. Up until this time I had been only speaking with Laticia, and when I saw her again that day she introduced me to her aunt who ran the restaurant. The aunt was a large boisterous woman who not only ran the restaurant but also –in some way– maintained a sizable influence in the neighborhood (though it was hard for me to determine because my Spanish is not very good.) I say this only because throughout the time that I was there many people came in to ask permission to speak to her. Leticia explained to her that I was a United States artist that wanted to come in and work for free for one night. She was amused by the idea and agreed to do it. We agreed on which night I should return and I left.

When the night arrived I put on black pants, white shirt, black shoes, black belt, and black tie and went to the restaurant. This is important because I wanted to mirror what I did in the United States as best as I could, and this is what I wear to work everyday. Also, the waitresses at the restaurant wore casual dress, so I must have looked quite out of place. I worked from 6 PM to 12 AM and –as I did in the United States– I cleared the tables, set the tables, and assisted the servers. When I was going home, I approached Leticia and tried to explain to her that in the United States the only reason that I worked in restaurants was so I could get cash tips. I told her that I had proved that I knew what I was doing and I wanted to return the next night, but this time I wanted to be paid one U.S. Dollar. I also tried to explain to her the story behind why I wanted to do this. After some time, she understood and I told her to think about it and the next day I would work a full day and she could answer me then. A shift at this restaurant is 13 hours long, beginning at 10 AM and ending at 12 AM the following day. The waitresses got paid one U.S. Dollar a day and any tips that were received were split evenly amongst all the employees.

Working on the first night.

The next day I went in at 10 AM as we discussed and things went smoothly. Although it turned out that Leticia was not working that day. At around 2 PM she came in and gave me –as a souvenir– 19 pesos made up of all different quantities of bills and coins. At the time, there were 21 pesos in one U.S. dollar. At the end of the night I had the dishwasher take my picture just like I had done in the United States, gave them my address, and left.

Busboy, Havana Cuba

Busboy, San Francisco, CA

I do not feel my project was a success though. This is due to the fact that I was comparing being a United States worker going to Cuba to work in a restaurant to the experience of my Mexican co-workers coming to the United States to do the same. In retrospect, this project will only work if I go to Mexico and do it. Further, I only received 19 pesos, which was two pesos under my goal. In the end, I received an amazing experience though. I got the chance to spend a good deal of time learning how the “Paladar” hustle worked, the dynamics of this extended family unit, and to experience the neighborhood as less of an outsider. As I think back on those 19 hours that I worked I see they were more about me and my attempts to understand a portion of my past and set that part to rest.

Cuban Money that I “Earned”

I saw a “ghost” while I was walking home after my first night working at the Paladar. As I walked, I felt guilty because I had asked for money. My intentions were never to go to this restaurant and work for charity’s sake. I went there as a United States citizen in search of a dollar. I felt badly because I was conscientiously doing the very things that my government had been doing for years and it made me tremendously sad. I felt cold, uncaring, and I feared that the people I had worked with thought I was just another U.S. citizen coming under false pretenses, saying that I wanted to help them, but, in reality all I wanted to do was profit from them (which was exactly what I was doing.) This guilt was reinforced by something that I had read a few days prior while combing through an old book store in Havana. My friend Steve Lambert found a copy of political discourses by famous Cuban thinkers that had both the Spanish and English translations side by side. In the book there was a famous letter written by José Martí, who was the ideological leader of Cuba’s first revolution against the Spanish colonization of the island. On March 23, 1894 –after spending time in New York– Martí gave a warning to the Cuban people about what the United States true intentions were when they offered to help Cuba in their revolution:

“It is sublime ignorance, of childish and punishable levity, to speak of the United States and of the real or apparent conquests of one or more groups of its states; as if they were a complete and equal nation of universal freedom and definitive victories. Such a United States is an illusion and fraud…The honest man cannot fail to notice that the original elements and different tendencies which created the United States have not only failed…(but has created) an unnatural federation into a state made harsh by violent conquest.” Martí, 1894

In 1896 the Cuban people began their first revolution to overthrow Spain’s occupation of their island. The United States came to Cuba’s aid and at the end of the war manipulated the Congress of Cuba to include in their constitution the Platt Amendment which gave the United States the right to intervene into Cuban affairs if it thought that “independence” was being threatened. The Cuban delegation heeded Martí’s warning, but it was too late. The United States army would not leave the island until the Cuban Congress ratified the act, and with its passing the United States exerted indirect control over Cuba for the next 60 odd years.

That night as I walked and remembered Martí’s dire poetic warnings, all of the profiteering that the United States government had allowed and promoted in Cuba filled my head and great fear washed over me. This was the first time I understood what a ghost really is. As a person who is a United States citizen, was raised in the suburbs, and is a white heterosecual man of mixed European decent, I have sensed this ghost for many years. For myself, the ghost had always manifested as a sense of disordered longing, stemming from being in a place life was supposed to be “good” and finding myself struggling emotionally, financially, and intellectually. It also came from an education that glorified the conquests of the United States while insisting that everyone has the right to make their own decisions. This went a step further by being told that my country was making every effort to ensure that the rest of the world will some day enjoy the luxuries and liberties that I enjoyed. The ghost rose again for me in my unique last name, which though is Southern Italian, is not a link to a strong heritage. My knowledge of family history on my fathers side is minimal. I have some minimal knowledge of some of my mothers heritage but for the most part my grandmother’s Polish history is dead and gone. My first name, Lucas, was found in a book of baby names. The ghost lives in me both mentally and physically. As I grew older, I had no idea what was wrong with the world. I sensed there was something wrong, but found it impossible to put my finger on it; I was very isolated and it was difficult to get reliable information. I worked a lot in Junior and Senior high school to financially help my family, and my parents thought that the reason why I was so depressed and quietly angry was because few of my peers had to do similar things. I now understand the part that I could never explain; the ghosts. The sensation that one feels as the result of their manifestation is best described by Avery Gordon in his book Ghostly Matters (1997) –which is a study of social hauntings– as, “…the wear and tear of long years struggling to survive; the exhausting anger and shame at patiently and repetitively explaining or irritably shouting about what can certainly be known but is treated as an unfathomable mystery…the quiet stranglehold of a full-time alertness to benevolent rule; and the virtually unspeakable loss of control, the abnegation, over is possible.”

Life without ghosts would be hard for me to image. It would be wonderful to be in control of how I interpret my visual landscape, instead of being at the every whim of these “supernatural” forces. It seems that to confront the ghosts the United States government must begin to take responsibility for its past actions. This seems unlikely though, so the only alternative is for each individual citizen of the United States to quietly and personally confront one of these ghosts and ask for its forgiveness. I am of the opinion that each United States citizen is directly responsible for the atrocities that our past leaders have committed, because everyday we directly profit from their past actions. Fidel Castro once wrote that history would absolve him. He meant that although the world may look at him in an unfavorable light now, when future generations look back and consider his actions he would find absolution. I do not believe I will be so lucky as a United States citizen who is pinned into in-action by fear and by the ghosts of Cubans, African Americans, Native Americans, Japanese, Mexicans…the list goes on and on. History will offer me no such absolution; my forefathers have acted maliciously on my behalf.

Lucas Murgida, November 2000, Havana Cuba